Anglo American Book, Rome’s oldest English-language bookshop – founded in 1953 by Dino Donati and run by the Donati family for 70 years – is shuttering for good this week. This is a profoundly sad piece of news, though not unexpected. Skyrocketing rents have buried yet another temple of culture.

I worked at the AAB for five years, from 2005 to 2011. Like the Gotham Book Mart before it, it was a unique place where I met many unforgettable people. One friendship I struck up at the AAB was with Alexander Booth. He would come in often, and we always got to talking about literature, music and Richmond, Virginia in the 1990s. (We had both gone to VCU, a year or so apart, and ended up expats in Rome.) Alex and I were (and very much still are) both poets and translators, and remain close friends to this day despite living in different countries. Alexander published a lively translation of the poetry of Sandro Penna a couple of years ago. I remember seeing it in the storefront window at AAB, not long before they moved to the windowless upstairs location removed from street traffic. Without the Anglo American, would we ever have met?

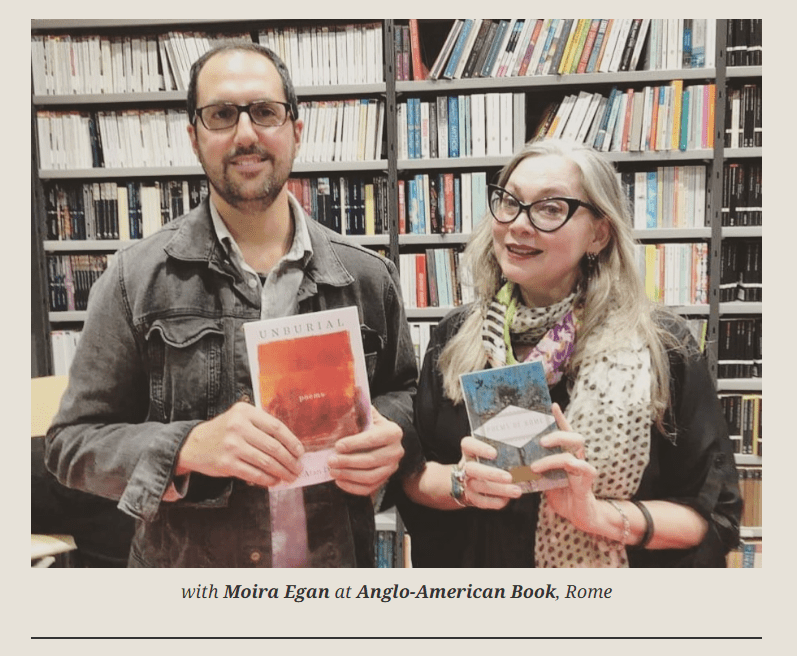

I remember the evening when we had just closed up and were turning off the lights, and two ghostly faces appeared at the door. It was poet Moira Egan and her husband, the translator Damiano Abeni. I had to tell them to come back during opening hours. We became friends over time, though, and I interviewed them for The American in 2009. When my first collection Unburial came out, Moira was gracious enough to partner with me for the book launch at AAB (photo above).

Here are the recordings of Moira and me reading on 12/7/2019 at the AAB:

Moira:

Marc:

___

It was also there that I met Mike Stocks, poet and translator of Giuseppe Gioacchino Belli. Mike walked in one day with a handful of copies of his newly published translation. Of course, I had to interview him. We went out for pints near Piazza Trilussa while I recorded our conversation on my wife’s handheld recording device. (This was pre-smartphone.) Mike revealed to me his secrets for approaching the great Romanesco poet, notoriously forbidding both for his 19th century Roman dialect and for the volume of his output: over 2000 sonnets (the critical edition of his poems runs over 5000 pages.) That meeting with Mike influenced my approach to translating Mario dell’Arco, convincing me that one didn’t need to have academic chops in order to get the job done. It was an important lesson, and if he hadn’t fallen off the grid I’d buy him a beer and thank him.

The list could go on, as lists do. Bookstores have played an outsized role in my adult life. It has been dawning on me for some time that I have lived at the edge of a disappearing era, a time when independent bookshops were places people went in their free time to meet other people, not unlike a neighborhood pub. They were like secular houses of worship. Relationships could be forged there. Lives could be altered. You were in the realm of curiosity, always bracing for the unexpected thrill of discovering a new book. Those born too late may never know this way of being in the world.

I spent many years working in bookshops on two continents: Strand, Gotham Book Mart, Anglo American Book. It was never a swank job with a good paycheck, but the summation of that experience was for me the equivalent of a university degree. I’ll always remember the names of people who worked at those NY bookshops before me: Tennessee Williams, Allen Ginsberg, Patti Smith, Tom Verlaine, Richard Hell. It seemed like it might almost be preparation for a future in the arts. Maybe it was.

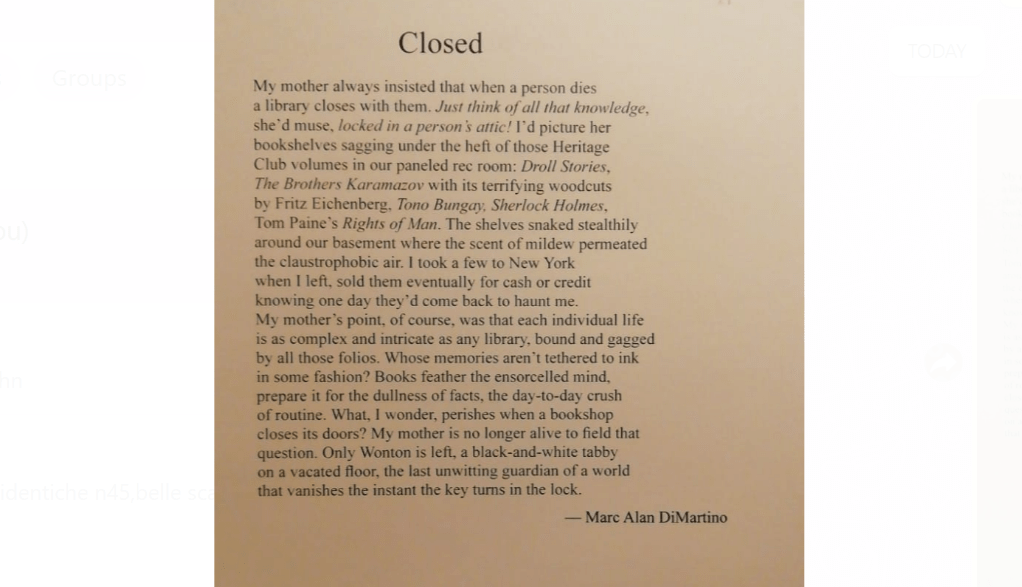

It seems apropos to round out this reminiscence with a poem about another of my favorite gone bookstores, Chop Suey Books in Richmond. It was my go-to bookshop whenever I was in town visiting the old haunts in Careytown. The poem was published in the Hollins Critic, a quirky little literary journal from Virginia which – but of course – ceased publication last year. It seems like our losses are neverending. All we have is art to push back against the rising tides of oblivion.