What I enjoy most as a translator is bringing poetry or poets to the English language for the first time. I have enormous esteem for the many translators of Dante, Belli, Montale and other Italian poets who have benefited from the efforts of a multitude of translators. Each new translation offers up a slightly – or drastically – different take on the same poem or author. Taken together, they create a composite portrait of the original work, not unlike reading multiple biographies of the same person written from different perspectives and points in history. But there are so many important voices still lurking in the shadows of literary history, stalking the margins, and that’s where I like to spend most of my time.

Much of my translation work has dealt with the poetry of Mario dell’Arco, a poet almost completely unknown in the English-speaking world a quarter century after his death. He is not much better known in his native Italy, or even in Rome, his birthplace. This despite the fact that he had a six-decade long career, published dozens of collections of original verse as well as versions of classical Roman poets like Martial and Catullus, and wrote books of prose including biographies of his Romanesco predecessors Belli and Trilussa. The point being, I noticed a gaping hole in the literature and made a conscious effort to fill it. My hope is that others may take up the gauntlet and try their hand at Dell’Arco, adding something to the portrait I’ve begun to sketch into English of this great poet’s work.

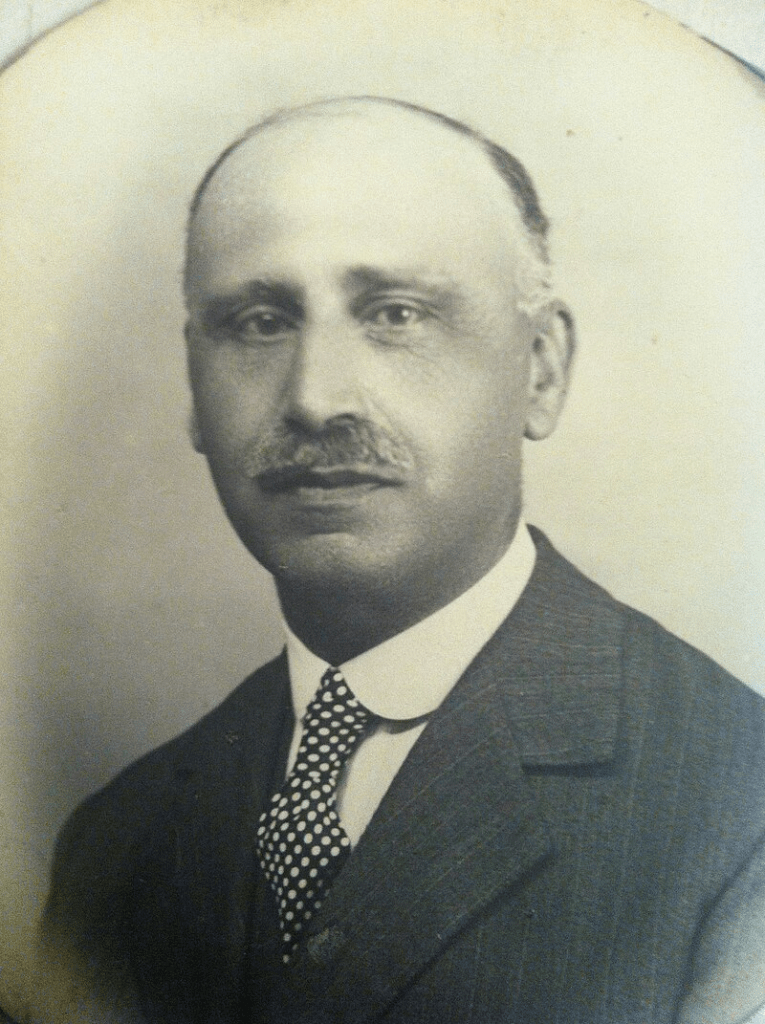

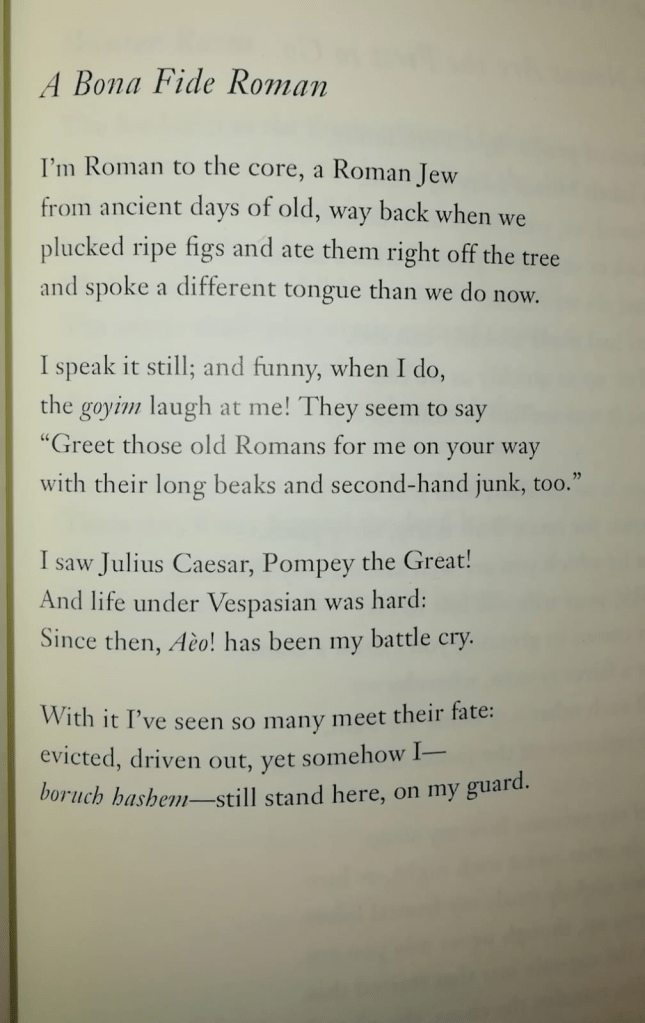

What has any of this to do with Crescenzo Del Monte, you ask? Well, Del Monte is another poet who has gone the way of the dodo, to put it bluntly. Yet he is arguably one of the five major Romanesco poets: Belli, Pascarella, Del Monte, Trilussa and Dell’Arco, in order of birth. Del Monte differed from the others in that he was Jewish, and wrote in Giudaico-Romanesco, the dialect of Roman Jews. He was a versatile writer who wrote in Romanesco and Italian as well, and did many translations of others’ work into Giudaico-Romanesco, such as a version of the first canto of Dante’s Inferno.

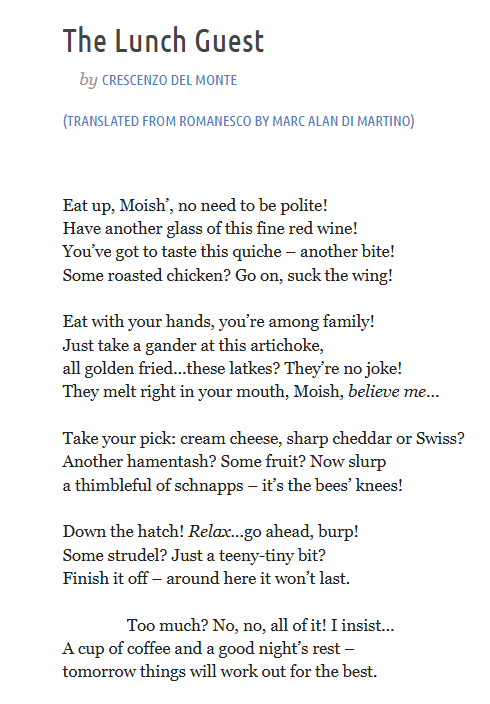

Like Belli, Del Monte can be forbidding because of his meticulous renderings of his characters’ actual speech patterns, as can be seen in “O’ ‘nvitato a pranzo” (below), and the surfeit of Hebrew words which are often half-masked through transliteration (chalomme is the Hebrew word for ‘dream’, חלום, pronounced chalom). Also like Belli, he offered up copious notes to his poems; practically every one has a glossary of terms to help the reader along. He knew it wouldn’t be easy, but he was preserving a world in his work, a world that now exists encoded in the poetry he wrote between the destruction of the Roman ghetto and the Fascist racial laws. (To hear a reading of Del Monte’s “La Cena de Purimme” – “Purim Dinner” – which bears a close resemblance in both theme and language to “The Lunch Guest”, including the same rhyme of chalomme/makomme, click here.)

I was lucky enough to have been able to study Hebrew in at the Jewish Cultural Center in Trastevere as well as in the ghetto, where for a time classes were being held in the local bookshop, Menorah. I’m by no means fluent, but I have enough of a grasp on the language and its historical-cultural milieu that I can find my way through the jungle with a candle and a machete.

As far as I know, there have been no other translations of Del Monte’s work into English. If I’m wrong, please reach out and let me know! Sgrùulla!

*an alternate ending to the above poem – one more faithful to the original – might read: A cup of coffee and then nighty-night/tomorrow it’ll end up in the toilet.

*line 8 of the above poem should read “with your long beak…”