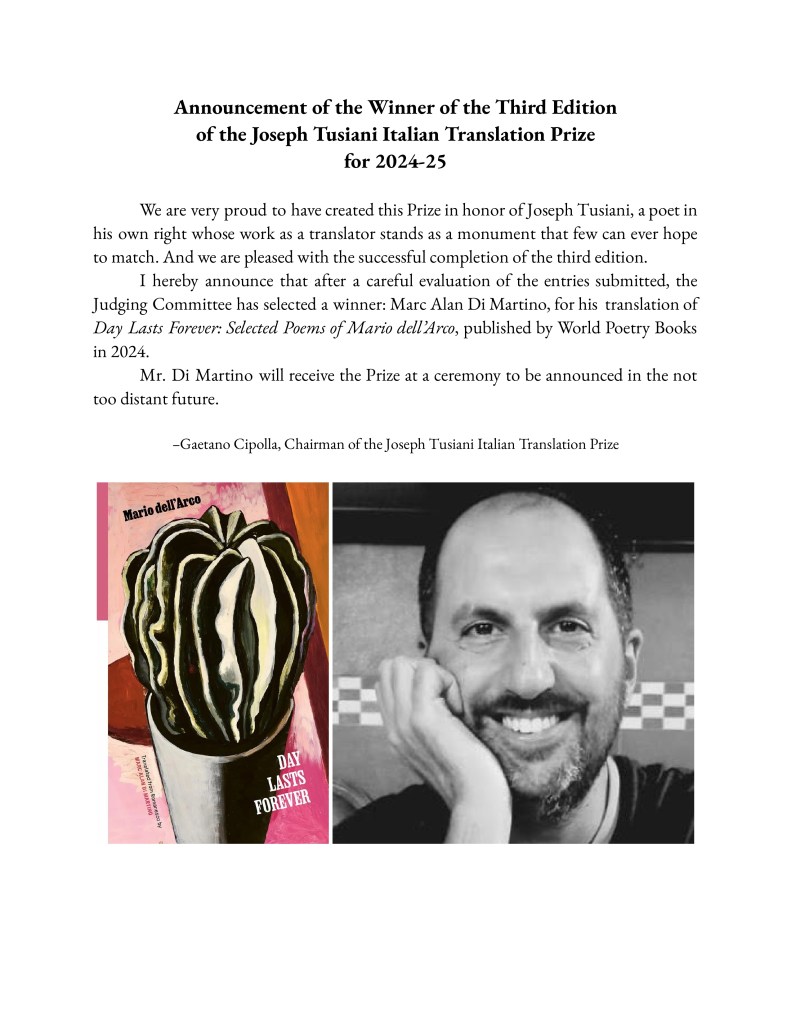

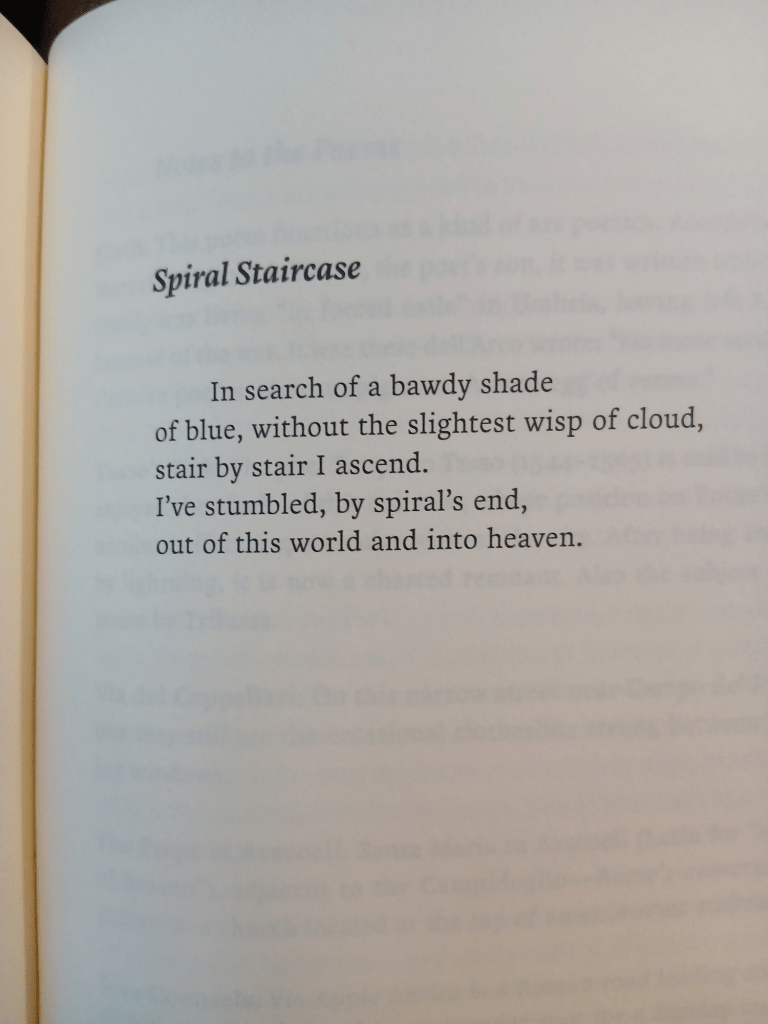

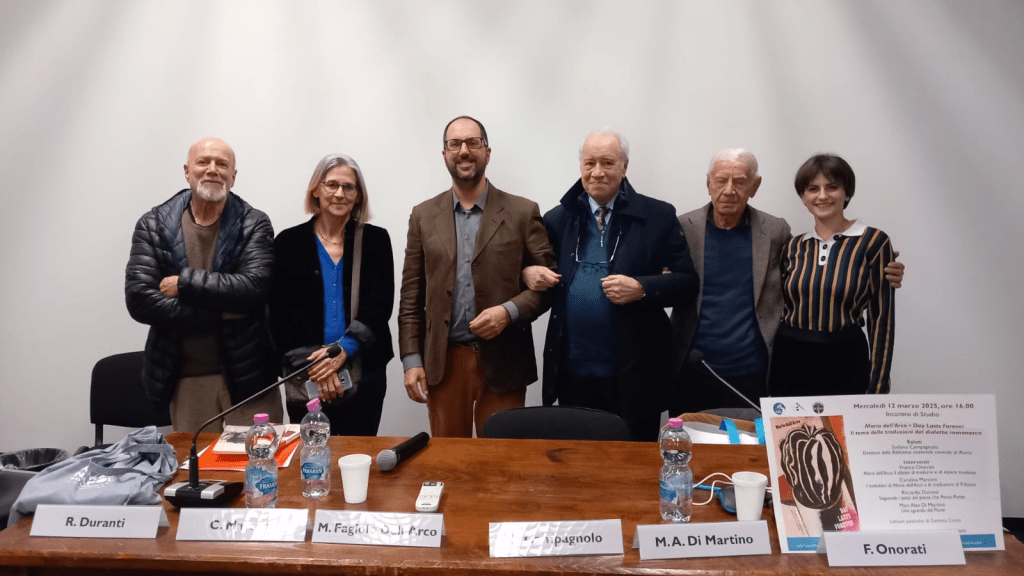

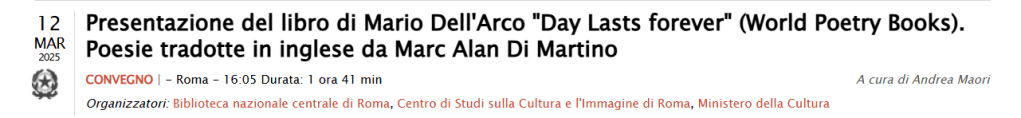

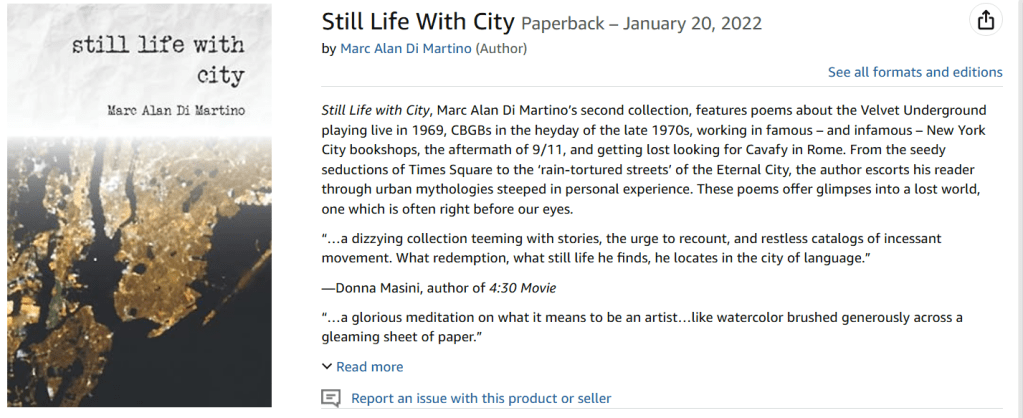

The good folks at One Art have generously published the very first of my translations of Romanesco poet Mauro Marè. I’ve been working diligently on these since late last year, and it has so far been a much different experience than that of translating Mario dell’Arco. With Dell’Arco, each poem is a kind of gemstone and the translation is performed like microscopic cutting, polishing the edges until they gleam. My approach to Marè has so far been the opposite—basically diving into his vision headfirst and learning to swim or perish in the thrashing current of bold juxtapositionings and idiosyncratic neologisms. The above painting by Italian artist Scipione (1904-33) is the subject of one of his early efforts, “Mamma Roma”, an ekphrastic sonnet whose title echoes Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1962 film of the same name. It hints at a Roman darkness and grotesqueness which Marè puts his finger on, especially in his later work of the ’80s and ’90s.

Marè’s publishing career was brief compared to Dell’Arco’s—a mere 20 years as opposed to the latter’s half century of dominance—but in his final decade he broke exciting new ground. It has been said to me by those in the know that Dell’Arco never once used a cuss word or profanity in his poetry. (If true, I am guilty of misrepresenting him in a single poem in which—inspired by Belli’s more profane moments—I put the ‘c’ word in the mouth of Santaccia, or St. Bad Girl, the infamous prostitute of Belli’s most gloriously dirty sonnets. [I justify my choice in a note on the poem, for those interested.]) In any case, Marè provides a jarring juxtaposition to Dell’Arco’s tame tongue, offering up a literal smorgasbord of romanaccio terms anyone with a passing familiarity with the Urbs will recognize: li mortacci tua, mmavvaffanculo, bbojja de mmerda, zzozzone etc…these are such colorful words, the verbal equivalent of Niki de Saint Phalle’s Shooting paintings, made by literally pointing a shotgun at her canvasses and blowing away pockets of colored paint. As a kid, I used to listen to my dad on the phone with his brother and sisters in Rome, and immediately grasped the unique lure of these interjections. They were my first words of Italian. Marè at times strings them together in zinging neologisms, the kind of thing one might hear from some drunk meandering though the streets at 2 a.m. cursing the world to the world: the bust driver, the Prime Minister, the Pope, all the way up to the throne of god.

There is a lot more to say about Marè and his poetry, which will surely be the subject of further posts.

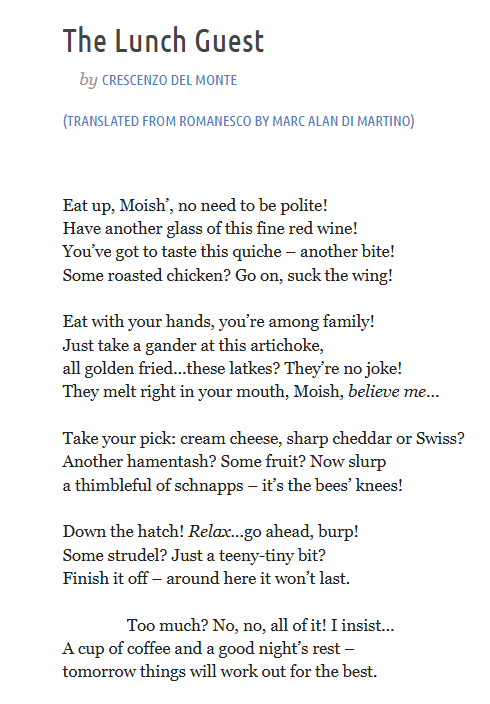

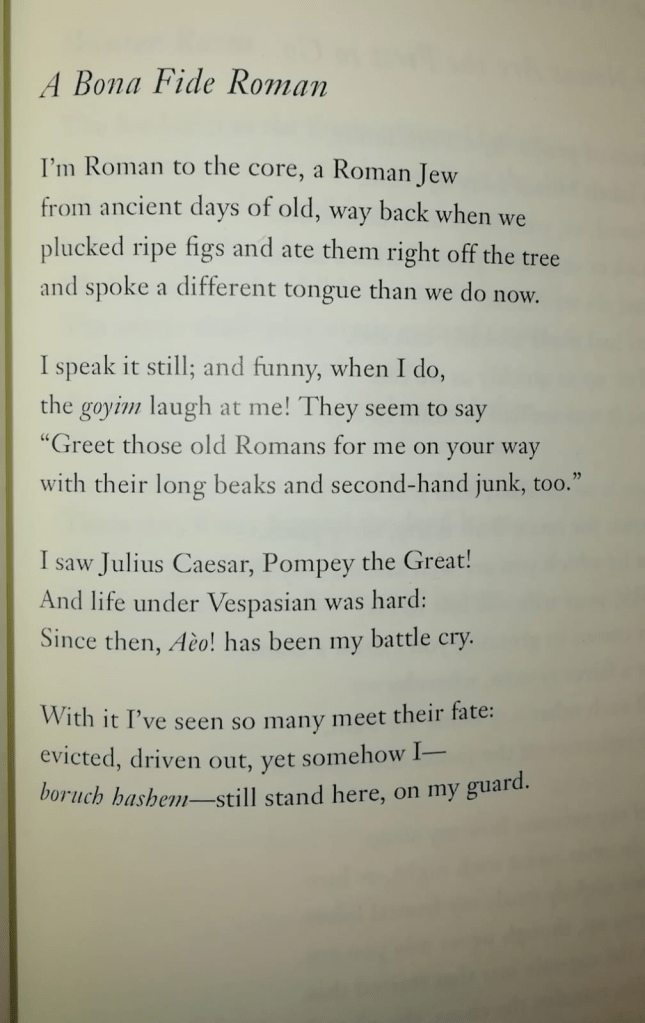

See also: Two Poems by Crescenzo del Monte