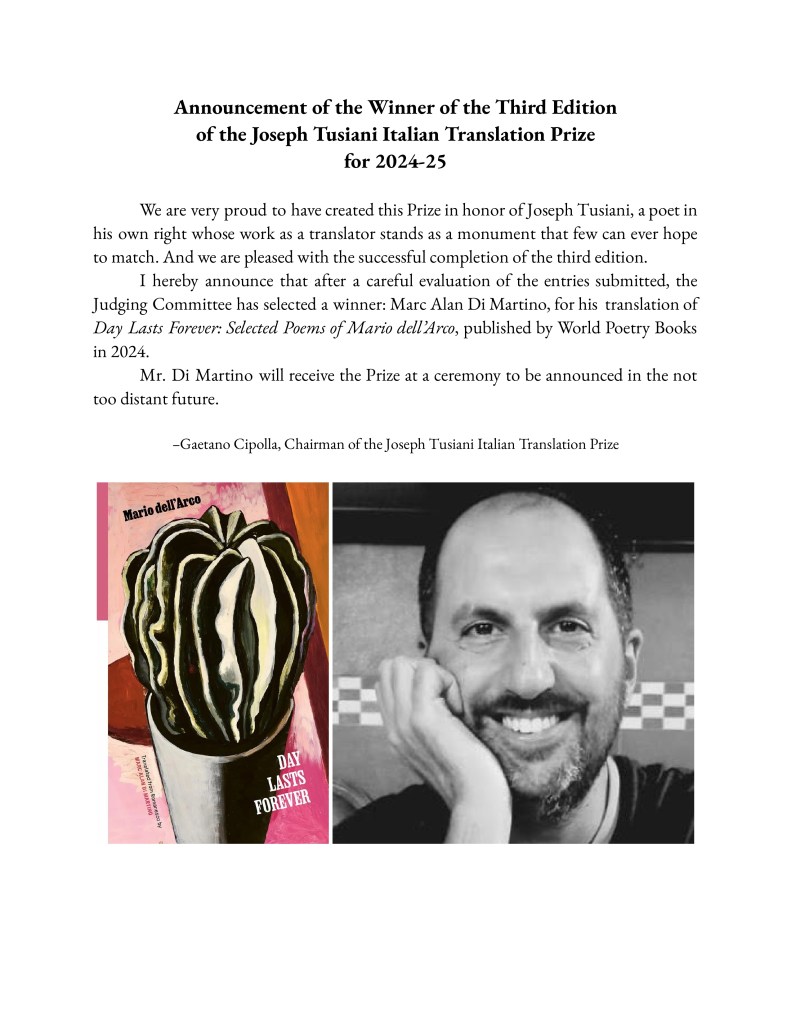

I have an exciting bit of news to share – Day Lasts Forever has won the Joseph Tusiani Italian Translation Prize for 2024-25! Below is the official announcement. The book can be ordered directly from World Poetry Books, from your local, preferably independent, bookseller or from anywhere that sells quality poetry books. An excellent review of the book by Jason Gordy Walker can be found at Asymptote. Another, by Anna Aslanyan, can be found in the Times Literary Supplement. You can read selections of Mario dell’Arco’s poetry at On the Seawall, Bad Lilies, Apple Valley Review and One Art. For Mario dell’Arco’s 120th birthday celebration at the National Library in Rome, see this post. Thank you to everyone who has supported this project! More to come!

poetry

“Dear Liz—” at the Shore

I’m extremely pleased to have a poem in the current issue of the Shore. “Dear Liz—” is a little love letter to Liz Phair’s first album, Exile in Guyville (1993). The poem was originally a shape poem, but it didn’t really work and so – after a few years and a few rounds of modifications – it settled into its current mode as a haibun. The allusion in the last lines is to the rock critic Robert Christgau, who must’ve written something memorable about the Rolling Stones that insinuated itself into the fabric of this poem.

Dear Liz—

you had me at ‘Fuck and Run’, your parched voice

like husks of sweet corn under a dying

August sun—Silver Queen, the only kind—all

sturm und twang, slight lisp betraying a shyness

undercut by your half-exposed nipple on the album

jacket. You drove us wild at nineteen, tired

of guys like ourselves running everything, screaming

their emo angst in our ears.

[read the whole poem at the Shore]

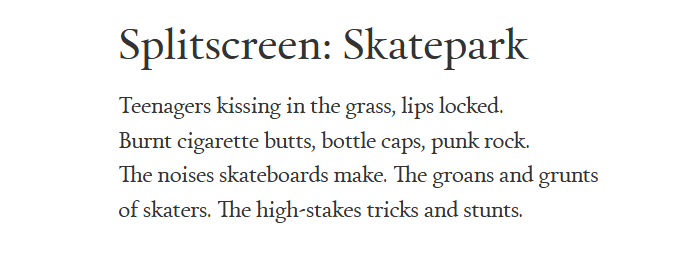

“Splitscreen: Skatepark” at Rust & Moth

I’m always thrilled to have a poem at Rust & Moth, which has one of the most reader-friendly presentations of any litmag out there. This poem is called “Splitscreen: Skatepark” and attempts to capture some of the sweat and grit of the local skatepark on a fine summer’s day. I spent my teenage years in such places, and the scene drawn in the poem is largely a composite of those languid afternoons, including one more recent episode viewed from my current perspective as an adult skateboarder that prompted the poem itself. For those keeping score, it’s a sonnet written in rhyming couplets.

If you like skateboarding poems, I have a few more at Loch Raven Review.

“Wildfire” at Sheila-Na-Gig

My poem “Wildfire” went live at Sheila-Na-Gig last week, a poem I wrote when I learned my uncle Osvaldo had been diagnosed with advanced-stage cancer. A couple of months later – if that long – he was gone. It was the beginning of a rough year of losses in our family, which then turned into the pandemic, etc…it feels like we’ve been on this rollercoaster for quite a while now, and I just learned the Pope died this morning as well. I’m an atheist, and was always rather skeptical of Pope Francis – as I am of all popes, and the institution they head – but he was always a better man than his predecessor. I hope his successor is better still, but I’m not holding my breath.

In any case, my uncle was a good man of conflicted religious nature who came to philosophy late in his life. We had a great many conversations on our walks in the woods together, just the two of us, and that is how I will always remember him. The last time we saw him, in the hospital, he was all smiles. May his memory be a blessing.

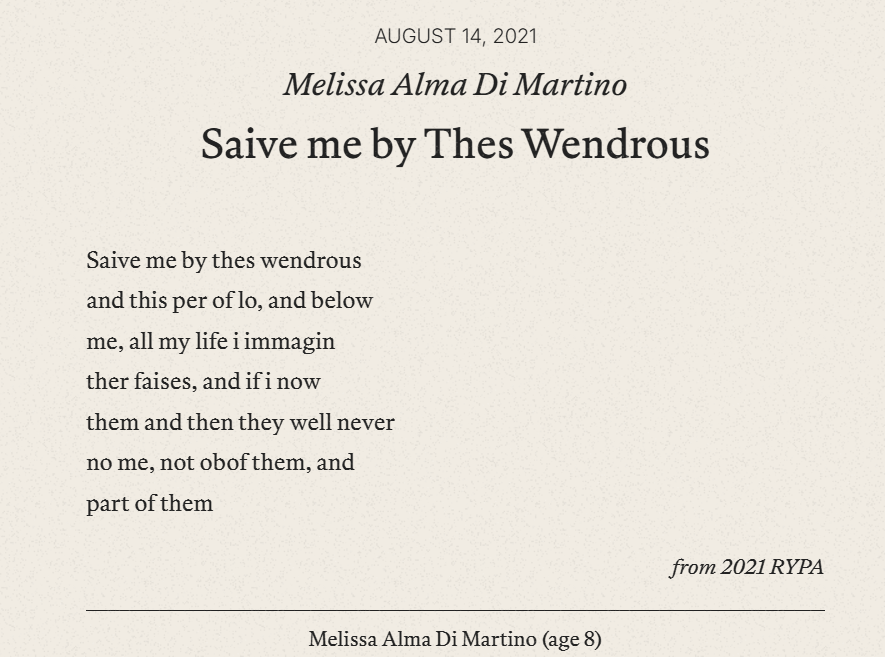

Saive Me by Thes Wendrous

April is National Poetry Month and there is no better way to celebrate it than by sharing a poem by my daughter. She wrote this short metaphysical poem when she was eight, and hasn’t written another one since. But what a poem! From the Rattle Young Poets Anthology 2021.

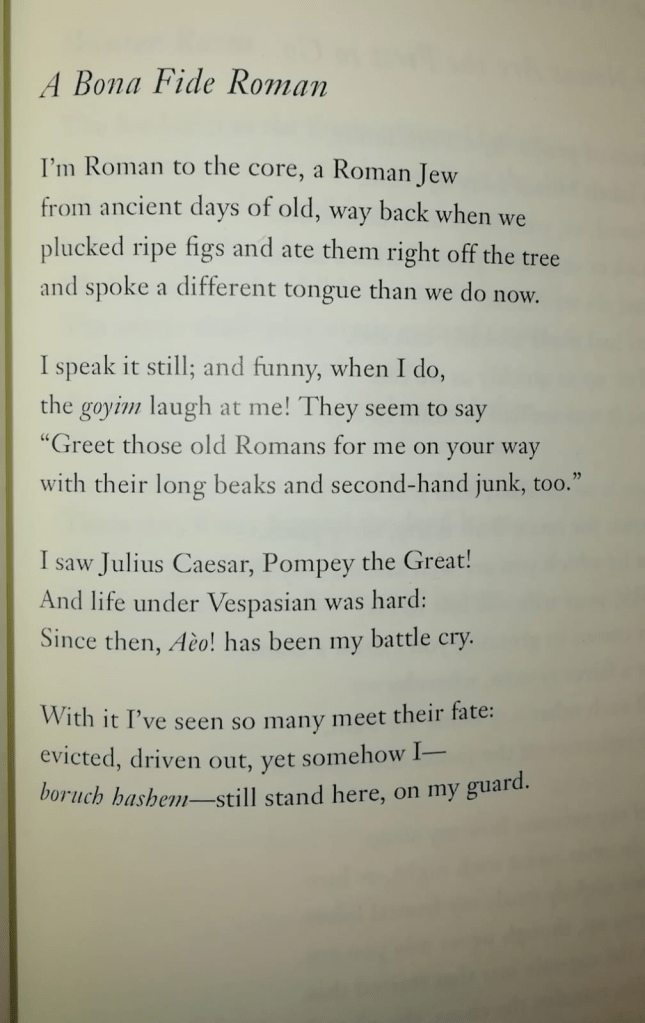

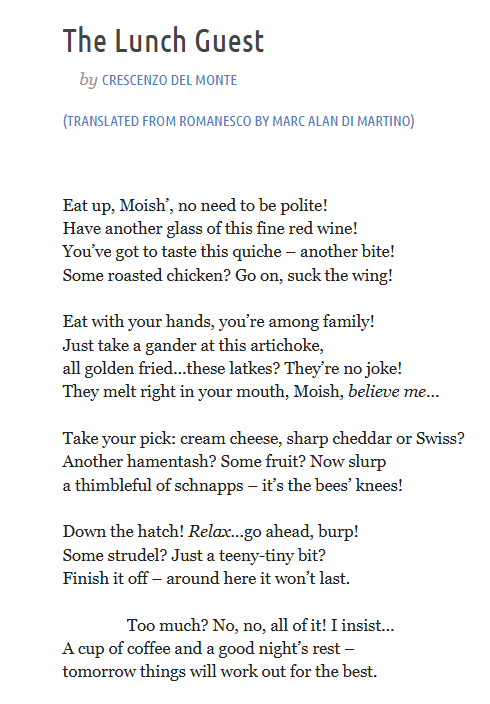

Two Poems by Crescenzo Del Monte

What I enjoy most as a translator is bringing poetry or poets to the English language for the first time. I have enormous esteem for the many translators of Dante, Belli, Montale and other Italian poets who have benefited from the efforts of a multitude of translators. Each new translation offers up a slightly – or drastically – different take on the same poem or author. Taken together, they create a composite portrait of the original work, not unlike reading multiple biographies of the same person written from different perspectives and points in history. But there are so many important voices still lurking in the shadows of literary history, stalking the margins, and that’s where I like to spend most of my time.

Much of my translation work has dealt with the poetry of Mario dell’Arco, a poet almost completely unknown in the English-speaking world a quarter century after his death. He is not much better known in his native Italy, or even in Rome, his birthplace. This despite the fact that he had a six-decade long career, published dozens of collections of original verse as well as versions of classical Roman poets like Martial and Catullus, and wrote books of prose including biographies of his Romanesco predecessors Belli and Trilussa. The point being, I noticed a gaping hole in the literature and made a conscious effort to fill it. My hope is that others may take up the gauntlet and try their hand at Dell’Arco, adding something to the portrait I’ve begun to sketch into English of this great poet’s work.

What has any of this to do with Crescenzo Del Monte, you ask? Well, Del Monte is another poet who has gone the way of the dodo, to put it bluntly. Yet he is arguably one of the five major Romanesco poets: Belli, Pascarella, Del Monte, Trilussa and Dell’Arco, in order of birth. Del Monte differed from the others in that he was Jewish, and wrote in Giudaico-Romanesco, the dialect of Roman Jews. He was a versatile writer who wrote in Romanesco and Italian as well, and did many translations of others’ work into Giudaico-Romanesco, such as a version of the first canto of Dante’s Inferno.

Like Belli, Del Monte can be forbidding because of his meticulous renderings of his characters’ actual speech patterns, as can be seen in “O’ ‘nvitato a pranzo” (below), and the surfeit of Hebrew words which are often half-masked through transliteration (chalomme is the Hebrew word for ‘dream’, חלום, pronounced chalom). Also like Belli, he offered up copious notes to his poems; practically every one has a glossary of terms to help the reader along. He knew it wouldn’t be easy, but he was preserving a world in his work, a world that now exists encoded in the poetry he wrote between the destruction of the Roman ghetto and the Fascist racial laws. (To hear a reading of Del Monte’s “La Cena de Purimme” – “Purim Dinner” – which bears a close resemblance in both theme and language to “The Lunch Guest”, including the same rhyme of chalomme/makomme, click here.)

I was lucky enough to have been able to study Hebrew in at the Jewish Cultural Center in Trastevere as well as in the ghetto, where for a time classes were being held in the local bookshop, Menorah. I’m by no means fluent, but I have enough of a grasp on the language and its historical-cultural milieu that I can find my way through the jungle with a candle and a machete.

As far as I know, there have been no other translations of Del Monte’s work into English. If I’m wrong, please reach out and let me know! Sgrùulla!

*an alternate ending to the above poem – one more faithful to the original – might read: A cup of coffee and then nighty-night/tomorrow it’ll end up in the toilet.

*line 8 of the above poem should read “with your long beak…”

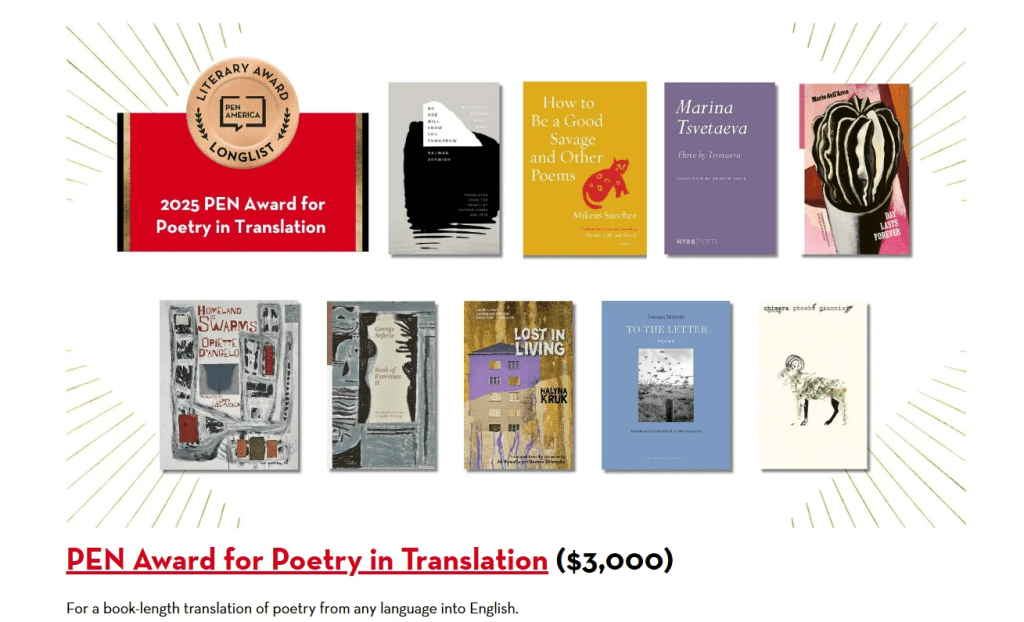

Day Lasts Forever *Longlisted* for the 2025 PEN Award for Poetry in Translation

This is exciting!

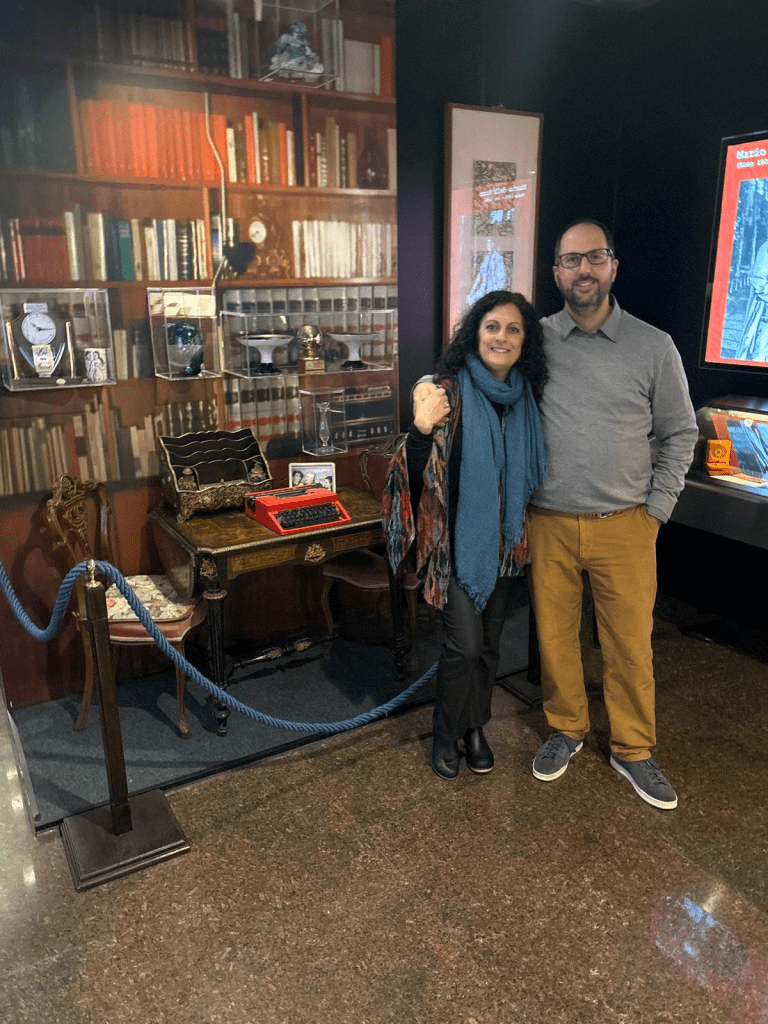

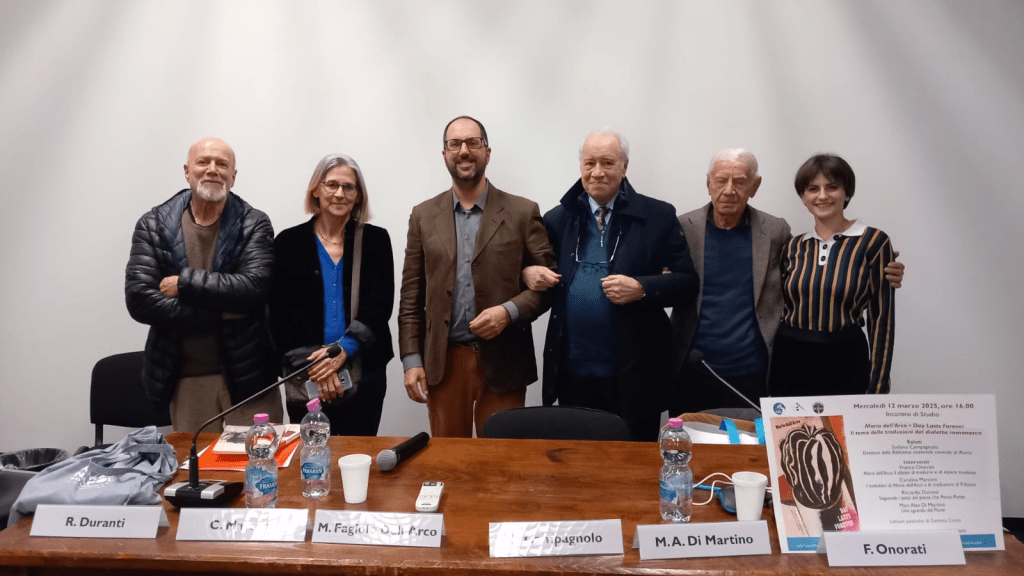

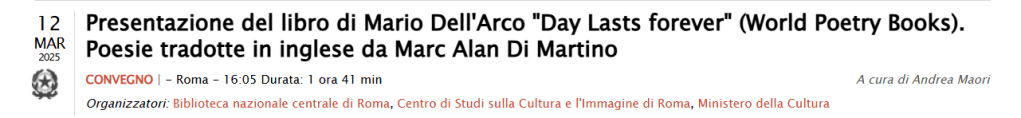

Day Lasts Forever at the Biblioteca Nazionale di Roma – March 12, 2025

Mario dell’Arco was born in Rome on March 12, 1905 in Via dell’Orso, not far from Piazza Navona. Last Wednesday would have been his 120th birthday. We spent it at the Biblioteca Nazionale di Roma (National Library of Rome) in Castro Pretorio, celebrating his poetry and his life. Ostensibly, much of this was also a celebration of Day Lasts Forever, which has the distinction of being the first book of Dell’Arco’s work to be translated into English or, to my knowledge, any other language. This has been cause for some celebration among the Romanisti – scholars and enthusiasts of Romanesco and its culture – as Dell’Arco was the last of the “four greats” of Romanesco poetry – Belli, Pascarella and Trilussa being the other three according to no less an authority on the subject than Leonardo Sciascia – to have ‘crossed the bridge’ into English.

I am honored to have been invited to participate in this conference, hosted by Marcello Fagiolo dell’Arco, the poet’s son. My co-presenters are all accomplished scholars of Romanesco poetry – and Dell’Arco’s work in particular – who have been doing incredible work for decades to get him the recognition he deserves, including erecting commemorative plaques in Via dell’Orso (above) and at Castel Sant’Angelo (below), where a section of the gardens now bears his name.

When I began reading and translating Dell’Arco’s work, I spent most of my time in a vacuum. I had no inkling any of this existed outside of a few books published for his centenary. Suddenly, now it feels like it must have felt for Dorothy when her house landed in Oz; the world has gone from black-and-white to Technicolor in a very short time.

There is so much I could say about the event. Each presentation was distinct and rich in detail, ranging from a biographical portrait of his father and the deeply personal nature of much of his work (Fagiolo dell’Arco) to the playfulness of Dell’Arco’s encounters with the Latin poets Martial, Catullus and Horace, which he ‘Romanescoed’ (Onorati), to the second lives of Dell’Arco and Trilussa in translation (Marconi) and reflections on the art of translation (Duranti). My contribution was an essay I wrote in Italian – no ChatGPT – about my experience discovering Dell’Arco’s work and attempting to usher it to the other side of the Atlantic by hook or by crook. The curious reader can listen to the entirety of the presentations, where they were recorded and archived for posterity by Radio Radicale (click image below). The presentations are, of course, in Italian with readings of Dell’Arco’s Romanesco poems by the wonderful Gemma Costa and in English translation by Riccardo Duranti and myself. (You can click on the names in the sidebar to skip to the English-language content if you wish.)

As an added bonus, my sister filmed a couple of videos of me reading my translations of the poems “I Built a Wall” and “Heads or Tails?”. You can read selections from the book here.

Finally – and I could go on! – the event received a write up in Rugantino, a satirical paper published in Romanesco, founded in 1848 with the newly won freedom of the press (click image below). Bbona lettura e bbon ascolto!

If you’d like to order Day Lasts Forever – Selected Poems of Mario dell’Arco, click this link or pester your local bookseller into ordering it.

Day Lasts Forever Reviewed in RHINO

Anthony Madrid has written a review of Day Lasts Forever for RHINO. This is the fourth review so far and the third in the month of February! Madrid has this to say:

This is my kind of thing. Seventy-one poems, all but one, this big: [pincer fingers emoji]. I just checked: almost every single poem is five lines. Many are four. So…epigrams!

Yes, epigrams! and some other things like short lyrics about cats and wine as well as laments for the loss of loved ones. Many of the poems are indeed five lines, though some push seven or eight lines. The thing to notice is just how much Dell’Arco packs into those few lines, a dense imaginative space. Madrid happily quotes five poems in full, and still manages a brief review. He takes issue with one poem, a translation of a translation of Martial. It’s fair game. Read the poems and decide for yourself.

Day Lasts Forever: Selected Poems of Mario dell’Arco can be ordered from World Poetry Books or from you finest local booksellers.

Peace for Ukraine

Today marks exactly three years since Putin launched his most recent war of aggression against Ukraine. The war is senseless – all wars may be said to be senseless, but this one takes the cake. According to the Kyiv Independent, Ukraine has lost roughly 46,000 troops since the invasion began. Russia has lost just shy of 900,000 among those killed and wounded. The number of Ukrainians injured – including civilians – runs into the hundreds of thousands, not to mention the kidnappings, rape and torture victims, and other atrocities perpetrated by the Russians on innocent Ukrainian citizens. May this war end soon, and may it end with justice for Ukraine. Слава Україні! Slava Ukraini!

Below are a few poems I wrote an published during the first months of the war. I repost them here by way of solidarity with Ukraine and its people, as well as those standing with Ukraine on the right side of history.